Thursday, June 6, 2019

Business with a cause

on

June 06, 2019

Maybe time has come for Nepali entrepreneurs to launch their own businesses with a social cause

In Bhuwaneswar of Odisha, India, is located a sprawling campus of the Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS). It houses around 25,000 tribal students, providing them with free education, accommodation and food. The founder of KISS is Achyuta Samanta, a 52-year-old bachelor who spent his childhood in abject poverty. After completing his MSc in chemistry, he taught at many colleges and also worked as a lab assistant. He first established Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology (KIIT) in 1992 with just Rs 5,000 he was able to save.

Some 18,000 students study at KIIT today, and it is one of the largest private universities in India. The profits accruing from this university is channelled to fund the education of tens of thousands of tribal children. “It’s quite simple. KIIT funds KISS,” Dr Samanta told the Readers’ Digest magazine in 2013.

Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS) provides free accommodation, food, healthcare and education from Class 1 to Post-Graduation level students from tribal communities, giving them vocational training. This would not have been possible if KIIT was not run in a professional way and was not generating profit.

Not only in South Asia, new ventures are coming up around the world to support many social causes. From health to education, from public transport to saving heritage, these social businesses are trying to prove that you can earn profit and at the same time channelize it for public good.

In Nepal, a pioneer ophthalmologist Dr Ram Prasad Pokharel adopted this model while opening over a dozen eye hospitals in different parts of the country under the aegis of Nepal Netra Jyoti Sangh (NNJS). In his book, Reaching the Unreached, Dr Pokharel recalls how Chaudhary family donated six bighas of land (adding 16 bighas of land later) to set up the Sagarmatha Chaudhary Eye Hospital (SCEH) in the eastern Tarai town of Lahan.

While CBM, a German organization, has contributed generously to establish and run the hospital, the land is being used to cultivate banana and other fruits to top up the income of the hospital that treats tens of thousands of people from Nepal and India every year.

The well-known Tilganga Eye hospital (now known as Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology) in Kathmandu is producing and selling high-quality, low-cost intra-ocular lenses abroad and channeling the profit to provide quality eye care services to poor Nepali citizens.

This is the same philosophy that has been adopted by READ NEPAL, another NGO that helps local communities build multi-purpose libraries. The local community will provide land in which the NGO will help build a library building with IT and other facilities. Besides catering to youth, women and senior citizens, the library is keen to generate income locally in order to finance its operating costs.

Prof Muhammad Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, defines social business as a business that is launched to solve a social problem by using business methods, including the creation and sale of products or services. In his book Building Social Business written jointly with Karl Weber, Prof Yunus describes two kinds of social businesses. One is a non-loss, non-dividend company devoted to solving a social problem. This is owned by investors who reinvest all profits to expand and improve the business. The second kind is a profit-making company owned by poor people, either directly or through a trust that is dedicated to a predefined social cause like Grameen Bank.

In Bhuwaneswar of Odisha, India, is located a sprawling campus of the Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS). It houses around 25,000 tribal students, providing them with free education, accommodation and food. The founder of KISS is Achyuta Samanta, a 52-year-old bachelor who spent his childhood in abject poverty. After completing his MSc in chemistry, he taught at many colleges and also worked as a lab assistant. He first established Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology (KIIT) in 1992 with just Rs 5,000 he was able to save.

Some 18,000 students study at KIIT today, and it is one of the largest private universities in India. The profits accruing from this university is channelled to fund the education of tens of thousands of tribal children. “It’s quite simple. KIIT funds KISS,” Dr Samanta told the Readers’ Digest magazine in 2013.

Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS) provides free accommodation, food, healthcare and education from Class 1 to Post-Graduation level students from tribal communities, giving them vocational training. This would not have been possible if KIIT was not run in a professional way and was not generating profit.

Not only in South Asia, new ventures are coming up around the world to support many social causes. From health to education, from public transport to saving heritage, these social businesses are trying to prove that you can earn profit and at the same time channelize it for public good.

In Nepal, a pioneer ophthalmologist Dr Ram Prasad Pokharel adopted this model while opening over a dozen eye hospitals in different parts of the country under the aegis of Nepal Netra Jyoti Sangh (NNJS). In his book, Reaching the Unreached, Dr Pokharel recalls how Chaudhary family donated six bighas of land (adding 16 bighas of land later) to set up the Sagarmatha Chaudhary Eye Hospital (SCEH) in the eastern Tarai town of Lahan.

While CBM, a German organization, has contributed generously to establish and run the hospital, the land is being used to cultivate banana and other fruits to top up the income of the hospital that treats tens of thousands of people from Nepal and India every year.

The well-known Tilganga Eye hospital (now known as Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology) in Kathmandu is producing and selling high-quality, low-cost intra-ocular lenses abroad and channeling the profit to provide quality eye care services to poor Nepali citizens.

This is the same philosophy that has been adopted by READ NEPAL, another NGO that helps local communities build multi-purpose libraries. The local community will provide land in which the NGO will help build a library building with IT and other facilities. Besides catering to youth, women and senior citizens, the library is keen to generate income locally in order to finance its operating costs.

Prof Muhammad Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, defines social business as a business that is launched to solve a social problem by using business methods, including the creation and sale of products or services. In his book Building Social Business written jointly with Karl Weber, Prof Yunus describes two kinds of social businesses. One is a non-loss, non-dividend company devoted to solving a social problem. This is owned by investors who reinvest all profits to expand and improve the business. The second kind is a profit-making company owned by poor people, either directly or through a trust that is dedicated to a predefined social cause like Grameen Bank.

Creating joy

Prof Yunus was awarded Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 jointly with the Grameen Bank, for lifting millions of people out of poverty through micro-finance in Bangladesh. In their book, Yunus and Weber wrote that investors in a social business can take back their original investment amount over a period of time they define. “Here, the workforce gets market wage with better-than-standard working conditions and social business is all about joy.

Once you get involved with it you continue to discover the unlimited joy in doing it,” they said.

Creating joy may not be a priority for Nepali businesses, but they can also allocate certain percentage of their profits in setting up social businesses as part of their corporate social responsibility. The government can help by making such investment tax-free.

Similarly, Non-Resident Nepalis—who have been investing in various sectors in Nepal and also donating to various social causes—can also allocate part of their funds to support social businesses. The Government of Nepal, too, can encourage such businesses by promulgating policies to support social causes and also setting up a seed fund to help social entrepreneurs.

Of course, such initiatives seem to be bearing fruit of late. Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) has joined forces with Sajha Yatayat to launch Sajha buses in the capital. After the defunct Sajha Yatayat was turned into a cooperative with the government’s loan as a share and was given independence on administrative matters, it came back to life. Largely thanks to the unflinching effort of Kanak Mani Dixit and his team, Sajha sold its land held in other places and purchased new buses to ply in Kathmandu. Even if they are not making a profit right now, they are playing a critical role in easing and improving the urban transport system in the capital. They also have a plan to turn the current Sajha-owned land in Pulchowk into a multi-purpose, state-of-the-art “SouthAsia Center.”

Back in Odisha, Achyut Samanta is working on to set up 20 KISS branches in the state’s tribal areas. And he has the dream of setting up a KISS branch in every state of India. “This is going to be contagious,” Dr Samanta told the Readers Digest. “When you’re doing something for others and not for yourself, everybody listens.”

Maybe time has come up for Nepali entrepreneurs to launch their own businesses with a social cause so that it benefits a large section of society, not a privileged few.

Prof Yunus was awarded Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 jointly with the Grameen Bank, for lifting millions of people out of poverty through micro-finance in Bangladesh. In their book, Yunus and Weber wrote that investors in a social business can take back their original investment amount over a period of time they define. “Here, the workforce gets market wage with better-than-standard working conditions and social business is all about joy.

Once you get involved with it you continue to discover the unlimited joy in doing it,” they said.

Creating joy may not be a priority for Nepali businesses, but they can also allocate certain percentage of their profits in setting up social businesses as part of their corporate social responsibility. The government can help by making such investment tax-free.

Similarly, Non-Resident Nepalis—who have been investing in various sectors in Nepal and also donating to various social causes—can also allocate part of their funds to support social businesses. The Government of Nepal, too, can encourage such businesses by promulgating policies to support social causes and also setting up a seed fund to help social entrepreneurs.

Of course, such initiatives seem to be bearing fruit of late. Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) has joined forces with Sajha Yatayat to launch Sajha buses in the capital. After the defunct Sajha Yatayat was turned into a cooperative with the government’s loan as a share and was given independence on administrative matters, it came back to life. Largely thanks to the unflinching effort of Kanak Mani Dixit and his team, Sajha sold its land held in other places and purchased new buses to ply in Kathmandu. Even if they are not making a profit right now, they are playing a critical role in easing and improving the urban transport system in the capital. They also have a plan to turn the current Sajha-owned land in Pulchowk into a multi-purpose, state-of-the-art “SouthAsia Center.”

Back in Odisha, Achyut Samanta is working on to set up 20 KISS branches in the state’s tribal areas. And he has the dream of setting up a KISS branch in every state of India. “This is going to be contagious,” Dr Samanta told the Readers Digest. “When you’re doing something for others and not for yourself, everybody listens.”

Maybe time has come up for Nepali entrepreneurs to launch their own businesses with a social cause so that it benefits a large section of society, not a privileged few.

The author is a BBC journalist based in London. Views expressed are his own

@bhagirathyogi

Fighting poverty

on

June 06, 2019

Challenge is to deliver ‘bikas’ at the doorsteps of extremely poor communities like Chepangs and help transform their lives by involving them at every level.

Nearly five years ago, when philanthropist Bishnu Gautam reached Kanda in Chitwan district after walking uphill for more than six hours, he could not believe there were such disadvantaged settlements in Nepal even after six decades of planned development. The village is mainly inhabited by Chepangs—one of the poorest communities in the country. They are at the bottom rung when measured in terms of food security, life expectancy and access to health services or education, among others.

Gautam saw a young girl looking for ‘bhyakur’ (a kind of wild fruit) as a replacement of food. He later came to know that she had delivered a child just two weeks back at her home since the nearest health post was five hours away.

Chepangs have been living in abject poverty for the past several decades. Though the country has moved from monarchy to a Republican system and passed through a decade-long armed struggle, there have been no visible changes in their lifestyles. They live in thatched huts and grow food like maize and millet that can barely support them for few months. For the rest of the year, either they will have to migrate or forage in the forest.

Period plans

Though Nepal embarked on the journey of periodic planning since 1956, it was only in the sixth plan (1981-85) that reducing poverty was stated as one of the development objectives. Till 1990, nearly 40 percent of the people lived below the so-called poverty line (that is USD 77 per capita, per annum). According to the World Bank, Nepal managed to halve the percentage of people living on less than $1.25 a day in only seven years, from 53 percent in 2003-04 to 25 percent in 2010-11. It is believed to have gone further down despite the devastating earthquakes that hit the country two years ago.

Remittance—the money sent home by millions of Nepalis working abroad—has been credited for the fast decline of poverty in the country. In the year 2000, the contribution of remittance to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) stood at two percent, which has gone up to around 30 percent last year.

“ Given the phenomenal rise in remittances, they are likely the primary engine behind the improvements in living standards witnessed in Nepal, both directly (households receiving remittances) and indirectly (increased labour income of those that remained). Despite the successful and rapid reduction in poverty, there is an urgent need to change Nepal’s development model,” said a recent study published by the Washington DC-based Bank.

What such a model would be remains a matter of debate, though. While proponents of the free market economy call for less role for the state and increasing role for the private sector, others argue that the state should have a predominant role in economic development as well as in delivering social equity and justice. Whatever the model, raising human development would be their common objective.

Regional divides

According to the Nepal Human Development Report (HDR) 2014, Nepal’s trends in human development over the past decade show overall improvement accompanied by considerable, often entrenched regional and social inequalities. Regions already behind in human development remain that way, although inequalities among regions have begun narrowing, the report said.

And, it has got repercussions on reducing poverty in the country. Human Poverty Index (HPI) is one of the tools to measure poverty among households. According to the UN, the HPI value for Nepal in 2011 was estimated at 31.12 The HPI measures average deprivation in three basic dimensions of human development—a long and healthy life, knowledge and a decent standard of living.

For many Nepalis, it still remains a distant dream.

Back in Kanda, Bishnu Gautam interacted with the members of the Chepang community and asked what their most pressing needs were. Though they needed khana, nana and chhana (ie food, clothes and shelter), they said that they wanted educational opportunities for their children. The Balram-Kumar hostel he constructed in memory of his two late sons now houses more than 160 children mostly from the Chepang, Tamang and Gurung communities.

The Laxmi Pratisthan has already constructed 63 houses for the local people by mobilising resources mainly from the Non-Resident Nepali community. The Pratisthan first brought trainers from Lamjung district and trained local youths in carpentry and masonry. The local youths then utilised those skills in building houses for their own community.

The Prastisthan is also providing training to local women and distributing seeds and beehives to the local people. It also provides them training on raising goats and growing foods. And, within the last couple of years, visible transformation can be seen among the entire community. So, what are the lessons learnt? According to Gautam, the main lesson is that lives of marginalised communities like Chepangs can be transformed through dedication, mobilising resources and targeted support. “Of course, we should shun from imposing our own ideology and help them to use their own capabilities,” he added.

The capability of the people to take opportunities for their survival or the economic and social improvements is usually described as ‘agency.’ In his book Changing Livelihoods: Essays on Nepal’s Development since 1990, Jagannath Adhikari argues that policies are needed to strengthen the agency of the people and to facilitate the work or the activities they have undertaken as individuals and groups.

“This might include helping women who are trying to migrate for labour jobs, facilitate the co-operative movement organised by small farmers in the marketing of vegetables and milk production, (or) help squatters in their organisational efforts to improve public safety and basic utilities like water supply and sanitation, among others,” he writes.

For over 60,000 Chepang population scattered in Chitwan and neighboring districts, periodic plans have brought little cheers. The ‘Praja Bikas Karyakram’ introduced during the Panchayat era targeted at their upliftment but failed to bring about any visible changes in their living standards. Even programs launched after the restoration of democracy in 1990 couldn’t reach the area which were several hours trek away from the nearest road.

Local level elections—that took place after nearly 20 years—have installed local leadership in most of the country that knows the problems being faced by local communities and are best placed to address them. Now, the challenge is to deliver ‘bikas’ at the doorsteps of extremely poor communities like Chepangs and help transform their lives by involving them at every level.

Lessons learnt by Bishnu Gautam in Kanda could be handy for policy makers as well as local leaders.

The author is a BBC journalist based in London. Views expressed are his own

Twitter: @bhagirathyogi

Published On: August 1, 2017 - https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/fighting-poverty/

Fun after 40

on

June 06, 2019

Unless Nepal is able to create significant number of jobs in agriculture, infrastructure and tourism labor migration to other countries won’t stop.

A popular Nepali song by Hemanta Rana says, “Sun saili saili pardesh baat ma aula, chalis katesi ramaula”, which roughly translates to “Dear beloved, I will return from abroad and will have fun after turning 40”. Millions of Nepali youths like Gaurav Pahari (who plays the protagonist in the music video) are leaving behind their beloved children and family to earn a living abroad, and with a dream of making their life comfortable after 40.

According to the Department of Labor, over two million Nepali youths are working abroad, mainly in the Gulf countries and Malaysia. This doesn’t include millions of others who work in Nepal’s southern neighbor, India. Remittance—the money sent home by migrant workers—contributes nearly 30 percent to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Emerging from the decade-long armed insurrection and acute political instability, remittance has emerged as one of the main sources of income that is sustaining the country’s economy.

But the recent diplomatic crisis in Qatar, which hosts over 400,000 Nepali workers, shows that too much dependence on remittance could bode ill for the country’s economy. As Qatar’s neighbors including Saudi Arabia attempt to isolate the gas-rich country, the number of Nepalis leaving for Qatar has declined sharply, according to official statistics.

A recent study by the World Bank also warned against what it called ‘too much dependence of Nepal on remittance’. The report entitled Climbing Higher: Toward a Middle-Income Nepal notes that the large scale of migration is not a sign of strength, but a symptom of deep, chronic problems. “While remittances are helping boost household expenditure, they are doing little directly to improve public service delivery. Consequently, the quality of education, health care, and infrastructure remains abysmal,” said the report, adding, “Perhaps the most detrimental aspect of large-scale migration is that it relieves the pressure on policy makers to be more accountable and to deliver results.”

With 20 governments in as many years, Nepali leadership has done little to create employment opportunities back home or to provide skills to over 1,500 youths who leave the country every day in search of work. Moreover, little attention has been paid to the huge social costs the Nepali society is incurring by sending its young people abroad.

Studies suggest that foreign migration is abetting internal migration in Nepal as returnee migrants want to move their families to district headquarters or town centers. There is shortage of agricultural laborers and Tarai districts now largely depend on workers from India to plant and harvest crops. While households are marked by lonely elders it has also overburdened women to shoulder both household and community activities.

A recent study entitled Labour Migration and the Remittance Economy: The Socio-Political Impact conducted by the Center for the Study of Labour and Mobility (CESLAM) notes that male migration has had both empowering and disempowering effects on women and their position in the household. “Family support, especially their husband’s, is a crucial factor in women’s participation in public life… At the same time, male migration also prevents women’s participation as their absence saddles them with many responsibilities.”

In the song “Sun saili…” when the protagonist tells his wife she is in his memory all the time, she can’t respond, and instead bursts into tears. Millions of Nepali women are facing a similar plight thanks to migration. The social cost of migration, thus, has been quite considerable as children can’t spend time with their dads, parents don’t find the company of their sons and daughters and wives miss their husbands very much.

Nepal has witnessed a sharp decline in fertility rate over past last two decades. Total fertility rate (defined as the number of children who would be born per woman) stood at 5.1 in 1991, which declined to 2.6 in 2011, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics. Such a sharp decline has been attributed to factors such as expansion of education, access to contraceptives and more importantly, huge number of male migration.

While on average one or two coffins land at the Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu every day carrying bodies of Nepali migrant workers who die—mostly of sudden cardiac arrest—in a foreign land, reports suggest that nearly 10 percent deaths of Nepali migrants are due to suicides. This is yet another example of the costs associated with the migrant economy.

Way forward

In order to move out of the ‘low-growth, high migration trap,’ the World Bank recommends four-point ‘comprehensive reforms’ agenda, namely: Breaking down policy barriers, Building new sources of growth, Revitalizing the existing sources of growth and Investing in people. The report notes that unleashing large investments in hydropower would be a game changer for Nepal. “It would not only lead to massive new investments and improved productivity, but has the potential to lift wages significantly, and help to partially reverse migration, and increase competitiveness in downstream industries.”

The World Bank study declared that a systematic assault is needed for Nepal to break the vicious cycle and create the right balance between job creation at home and exports of labor.

With the first phase of the local level election taking place after nearly 20 years, a sort of enthusiasm can be seen across the country. But uncertainty facing the second phase and row over the constitution still pose challenges in the short term. In the long term, the challenge would be to find adequate capital and skilled manpower to build infrastructure and create employment opportunities.

Unless Nepal is able to create significant number of jobs especially in agriculture, infrastructure and tourism sectors, huge population will continue to migrate out of the country. Unfortunately, burdened with debt and growing uncertainty in their work destinations, they may not be able to realize their dream of having fun after they turn 40.

The author is a BBC journalist based in London. Views expressed are his own

Twitter: @bhagirathyogi

Published on : https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/fun-after-40/

Giving: The Nepali way

on

June 06, 2019

Generating resources locally and deploying them in a sustainable way warrants both strategic planning and clarity of purpose

Gyan Singh Tharu, who works as a peon at the Mahendra Campus at Bharatpur, Dang, decided to donate over Rs one lakh to construct a new building at the Padmodaya Public Model Higher Secondary School in Dang where he had his initial schooling.

Gyan Singh Tharu, who works as a peon at the Mahendra Campus at Bharatpur, Dang, decided to donate over Rs one lakh to construct a new building at the Padmodaya Public Model Higher Secondary School in Dang where he had his initial schooling.

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

Where’s the money?

on

June 04, 2019

Coming up with $24 billion over the next ten years is going to be a Himalayan challenge for Nepal

Minister for Energy, Janardan Sharma, said last month that the government aims to generate 17,000 MW of power within the next seven years. He said out of that 8,000 MW would be generated by the projects under government supervision and the rest by the private sector.

This ambitious announcement surpasses the government’s own commitment, expressed during the Nepal Power Summit 2016, when the Government of Nepal (GoN) set a target of 10,000 MW in 10 years. This means that the country will need an investment of approximately US $24 billion during this period.

According to the Nepal Banking Association, the amount available (for investment in hydropower sector) over the next 10 years in the Nepali banking sector is around $2 billion only. A handbook entitled “Opportunities for UK businesses in Nepal’s hydropower sector,” published by the British Embassy in Kathmandu, estimates that Development Finance Institutions may be able to allocate $2 billion, most of it coming from the International Finance Corporation (IFC)—a member of the World Bank group. Assuming domestic equity of approximately $3 billion, this leaves an additional Foreign Direct Investment financing requirement of $17 billion.

During the Nepal Investment Summit in March this year, foreign investors made a pledge of over $13 billion in different sectors including hydropower. While China came at the top by pledging $8.2 billion, power-hungry Bangladesh stood second with its pledge of $2.4 billion. Investors from Japan and the United Kingdom pledged over $1 billion each. Meanwhile, investors from the southern neighbor, India, committed $317 million.

It’s not clear how much of that pledge will actually materialize, given the fragile political situation in the country, but coming up with $24 billion over the next ten years is going to be a Himalayan challenge for Nepali officials, to say the least.

Over the past one decade, the installed capacity in Nepal has increased by around 50 MW per year; last year, it increased by 150 MW. Thus an increment of 1,000 MW per year looks highly ambitious, if not impossible. A World Bank report suggests that 10,000 MW is possible but that it would take 15-20 years.

Projects under construction

According to officials, Nepal now has 2,200 MW of projects under construction and projects with a combined capacity of over 1,000 MW have got generation license, while projects with the capacity of nearly 5,500 MW are seeking license. Finding money to develop all these projects is a real challenge.

On March 22, 2017, the Lord Mayor of London, Andrew Parmley, hosted at his office a meeting of British investors, businessmen, leaders of the Non-Resident Nepali community and Nepali officials.

Addressing the meeting, Industry Minister Nabindra Raj Joshi said the GON will go the extra mile to facilitate foreign capital and technology in different sectors including hydropower. He said the government was looking to enter into Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement with the UK, among others, and promised every possible help to British investors.

A study conducted by the Dolma Development Fund with support from British Aid Agency, DFID, in 2014 concluded that hydropower is the most attractive sector for investors in Nepal, and that there is great potential to grow in the renewable energy space. The study identified increasing domestic demand fuelled by rising income levels, industrial growth and government focus on energy sector as key growth drivers for grid power in Nepal. The study, however, warned that there are some infrastructural and regulatory challenges that the government needs to resolve in near future.

For British investors, Nepal offers an attractive investment destination. According to the British Embassy handbook, the approximate value of the hydro market in Nepal is in the region of $20.33 billion. Using the more realistic scenario of 8,700 MW in 15 years and assuming a 10 percent market share, British companies could aim for annual turnover of $13-$106 million, according to the handbook.

And, recent experience of Indian Masala bond could be interesting for prospective investors. In March this year, the Housing Development Finance Corp (HDFC), one of India’s leading banking and financial services companies, floated what is being called Masala bond at the London Stock Exchange (LSE). The HDFC was able to raise INR 33 billion (approx. $504 million) by floating the 37-month dated Rupee-denominated bond with an annual yield of 7.35 percent. Both Asian and European investors expressed their interest in the bond and it was more than two times oversubscribed.

Tim Gocher, founder of Dolma Impact Fund—the first international private equity fund dedicated to Nepal—believes that British and Nepali investors, backed by both the governments, can float similar bonds at the LSE to raise capital to invest in Nepal’s hydropower sector.

But the risk of attracting such money from international market is that you will have to start paying interest from Day One. If you can’t complete the project on time and can’t negotiate a favorable rate with the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA)—the monopoly buyer—return on investment would be uncertain. While you will need transmission lines to be ready to evacuate power from the completed projects, you will also need a neighboring market to sell the power after Nepal’s domestic electricity demand is met.

In October 2014, the governments of Nepal and India concluded a Power Trade Agreement (PTA) to enable cooperation on a number of power sector activities including transmission interconnections, grid connectivity, power exchange and trading. The PTA gives Nepal access to the Indian power market, though it is not clear if India would be happy to buy power generated by companies other than those involving its own investors.

Writing in The Hindu recently, former member of the Planning Commission of India Kirit Parikh observed that building hydropower projects and transmission infrastructure is highly investment-intensive. “Without a stable, long-term conducive policy and an institutional environment in place, which ensures payment security, it is unlikely that investors will put their money in this risky business.”

It’s high time Energy Minister Janardan Sharma and mandarins at the Ministry of Energy heed such advice before making high-sounding announcements.

Minister for Energy, Janardan Sharma, said last month that the government aims to generate 17,000 MW of power within the next seven years. He said out of that 8,000 MW would be generated by the projects under government supervision and the rest by the private sector.

This ambitious announcement surpasses the government’s own commitment, expressed during the Nepal Power Summit 2016, when the Government of Nepal (GoN) set a target of 10,000 MW in 10 years. This means that the country will need an investment of approximately US $24 billion during this period.

According to the Nepal Banking Association, the amount available (for investment in hydropower sector) over the next 10 years in the Nepali banking sector is around $2 billion only. A handbook entitled “Opportunities for UK businesses in Nepal’s hydropower sector,” published by the British Embassy in Kathmandu, estimates that Development Finance Institutions may be able to allocate $2 billion, most of it coming from the International Finance Corporation (IFC)—a member of the World Bank group. Assuming domestic equity of approximately $3 billion, this leaves an additional Foreign Direct Investment financing requirement of $17 billion.

During the Nepal Investment Summit in March this year, foreign investors made a pledge of over $13 billion in different sectors including hydropower. While China came at the top by pledging $8.2 billion, power-hungry Bangladesh stood second with its pledge of $2.4 billion. Investors from Japan and the United Kingdom pledged over $1 billion each. Meanwhile, investors from the southern neighbor, India, committed $317 million.

It’s not clear how much of that pledge will actually materialize, given the fragile political situation in the country, but coming up with $24 billion over the next ten years is going to be a Himalayan challenge for Nepali officials, to say the least.

Over the past one decade, the installed capacity in Nepal has increased by around 50 MW per year; last year, it increased by 150 MW. Thus an increment of 1,000 MW per year looks highly ambitious, if not impossible. A World Bank report suggests that 10,000 MW is possible but that it would take 15-20 years.

Projects under construction

According to officials, Nepal now has 2,200 MW of projects under construction and projects with a combined capacity of over 1,000 MW have got generation license, while projects with the capacity of nearly 5,500 MW are seeking license. Finding money to develop all these projects is a real challenge.

On March 22, 2017, the Lord Mayor of London, Andrew Parmley, hosted at his office a meeting of British investors, businessmen, leaders of the Non-Resident Nepali community and Nepali officials.

Addressing the meeting, Industry Minister Nabindra Raj Joshi said the GON will go the extra mile to facilitate foreign capital and technology in different sectors including hydropower. He said the government was looking to enter into Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement with the UK, among others, and promised every possible help to British investors.

A study conducted by the Dolma Development Fund with support from British Aid Agency, DFID, in 2014 concluded that hydropower is the most attractive sector for investors in Nepal, and that there is great potential to grow in the renewable energy space. The study identified increasing domestic demand fuelled by rising income levels, industrial growth and government focus on energy sector as key growth drivers for grid power in Nepal. The study, however, warned that there are some infrastructural and regulatory challenges that the government needs to resolve in near future.

For British investors, Nepal offers an attractive investment destination. According to the British Embassy handbook, the approximate value of the hydro market in Nepal is in the region of $20.33 billion. Using the more realistic scenario of 8,700 MW in 15 years and assuming a 10 percent market share, British companies could aim for annual turnover of $13-$106 million, according to the handbook.

And, recent experience of Indian Masala bond could be interesting for prospective investors. In March this year, the Housing Development Finance Corp (HDFC), one of India’s leading banking and financial services companies, floated what is being called Masala bond at the London Stock Exchange (LSE). The HDFC was able to raise INR 33 billion (approx. $504 million) by floating the 37-month dated Rupee-denominated bond with an annual yield of 7.35 percent. Both Asian and European investors expressed their interest in the bond and it was more than two times oversubscribed.

Tim Gocher, founder of Dolma Impact Fund—the first international private equity fund dedicated to Nepal—believes that British and Nepali investors, backed by both the governments, can float similar bonds at the LSE to raise capital to invest in Nepal’s hydropower sector.

But the risk of attracting such money from international market is that you will have to start paying interest from Day One. If you can’t complete the project on time and can’t negotiate a favorable rate with the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA)—the monopoly buyer—return on investment would be uncertain. While you will need transmission lines to be ready to evacuate power from the completed projects, you will also need a neighboring market to sell the power after Nepal’s domestic electricity demand is met.

In October 2014, the governments of Nepal and India concluded a Power Trade Agreement (PTA) to enable cooperation on a number of power sector activities including transmission interconnections, grid connectivity, power exchange and trading. The PTA gives Nepal access to the Indian power market, though it is not clear if India would be happy to buy power generated by companies other than those involving its own investors.

Writing in The Hindu recently, former member of the Planning Commission of India Kirit Parikh observed that building hydropower projects and transmission infrastructure is highly investment-intensive. “Without a stable, long-term conducive policy and an institutional environment in place, which ensures payment security, it is unlikely that investors will put their money in this risky business.”

It’s high time Energy Minister Janardan Sharma and mandarins at the Ministry of Energy heed such advice before making high-sounding announcements.

The author is a BBC journalist based in London. Views expressed are his own

Twitter: @bhagirathyogi

Saturday, February 2, 2019

एउटा ऐतिहासिक यात्रा

on

February 02, 2019

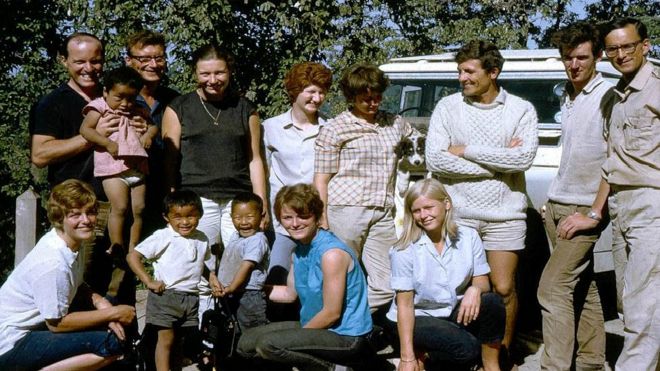

५० वर्षअघि नेपाल आएको ब्रिटिश चिकित्सक र नर्सहरूको समूहको सम्झना

भगीरथ योगीबीबीसी न्यूज नेपाली

साँचो अर्थमै त्यो एउटा ऐतिहासिक यात्रा थियो।

साँचो अर्थमै त्यो एउटा ऐतिहासिक यात्रा थियो।

पचास वर्षअघि सन् १९६८ को एप्रिल महिनामा ब्रिटिश चिकित्सक र नर्स सम्मिलित ११ जनाको एउटा टोली सेता ल्यान्ड रोभर जीप चढेर ब्रिटेनको दक्षिणी सीमासम्म पुग्यो।

ती जीपलाई फ्रान्स पुर्याइयो। त्यहाँबाट तिनै जीप चढेर सो टोली स्थलमार्ग हुँदै नेपालतिर हिँड्यो।

स्थलमार्गबाट किन त?

सो यात्रामा सहभागी डक्टर बार्नी रोस्डेलका अनुसार आर्थिक कारणले गर्दा स्थलमार्ग रोजिएको थियो।

तीनवटा गाडी लिएर नेपाल जाँदा ६०० पौन्ड खर्चले पुग्थ्यो भने पानीजहाज प्रयोग गर्दा २,००० पौन्ड लाग्थ्यो।

यात्रा युरोपबाट इस्तान्बुल र बोस्फरस हुँदै एशियातिर अघि बढ्यो।

थप यो लिङ्कमा

https://www.bbc.com/nepali/news-46434980

Friday, February 1, 2019

Getting back on track

on

February 01, 2019

Perpetual delays in legislation and implementation on road safety will cost more lives

-

Jan 20, 2019-

Pradip Ghimire, 31, was one of the much-sought-after teachers in Dang. After completing an MSc in Botany from Tribhuvan University five years ago, Pradip returned to his home district to work as a teacher. As there were very few teachers who were qualified to teach Botany, Pradip was teaching at nine different colleges in the district.

On 21st December, 37 people including, 32 students of the Ghorahi-based Krishna Sen Ichhuk Technical School, were returning to Ghorahi after a tour of a botanic garden at Kapurkot in Salyan district. 23 of them—mostly teachers and students—died when the bus they were travelling in fell off the road. The driver of the vehicle was among the deceased.

To read the full article, pls go to....

http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2019-01-20/getting-back-on-track.html

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)